Roy Halladay died way too young in a plane crash on Tuesday. This is the worst sort of news, and the entire baseball world just felt numb yesterday. There have already been plenty of wonderful tweets and columns on his career and untimely passing that hit the mark way better than I could so that’s not what I’m going to do here today. Plus, I’m not qualified to do that. I missed most of Halladay’s brilliance, since the bulk of his career was spent with Toronto in the American League.

My limited exposure to Halladay occurred when he was in a Phillies uniform the last few seasons of his career and pitching against the Cardinals, and all I can say is that he was terrifying. Without doing a deep numbers dive, I was more afraid of him in 2010 and 2011 than I have been of Clayton Kershaw, Madison Bumgarner, or any other recent pitcher you want to name. He felt invincible. That the Cardinals beat him in Game 5 of the 2011 NLDS, on the strength of Rafael Furcal and Skip Schumaker, no less, still doesn’t quite seem possible.

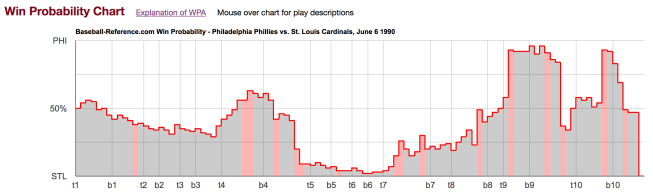

It seems unfair to Halladay that many on the Cardinals side of the aisle first conjure up Game 5 when thinking of his legacy since it was a game that he lost, but when something like this happens it’s only natural to reach into one’s own memory bank and that was one of the most thrilling nine innings of baseball most of us have ever seen. I recommend visiting Viva El Birdos if you want to read some great pieces on that game. And, it’s not at all an insult because what helped make that game so special was Halladay’s obvious dominance.

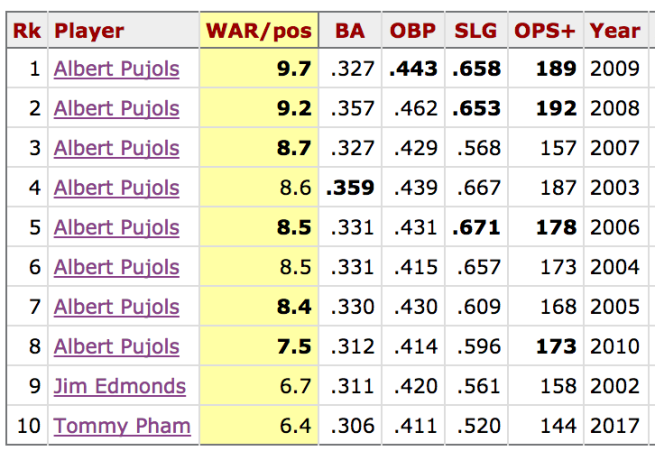

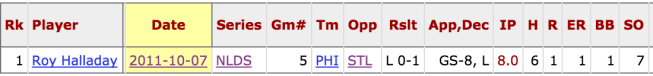

He pitched eight strong innings, struck out seven, walked only one batter (and it was an intentional pass to Albert Pujols – who had a career .461 OPS against Halladay), and allowed just a single run. That run, of course, turned out to be enough for the Cardinals, and Halladay got the “loss” as a result of baseball’s unfair and sometimes antiquated ways.

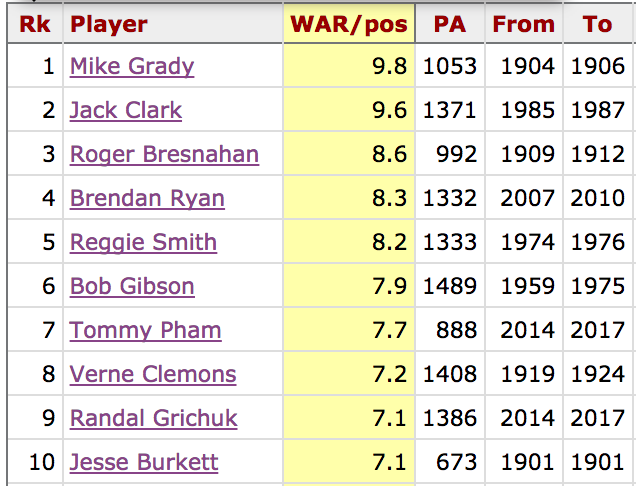

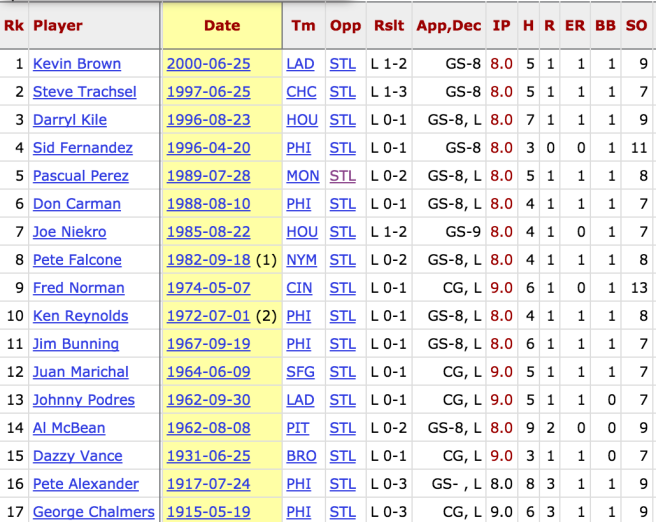

But take a look at that pitching line again. From Baseball Reference’s Play Index, here’s how many times the Cardinals have won a regular season 9-inning game (dating back to 1913) when the opposing pitcher matched or topped that line and took the loss:

Over 100 years of data and that’s the entire list. And, no shock, if you want to limit the search to just the postseason then this is all that you will find:

Game 5 was a true gem. And let’s be clear: the Cardinals didn’t really beat Roy Halladay that night. They just got lucky that Chris Carpenter was pitching, too. Rest in peace, Doc, you were one of the best.

Credit to Baseball Reference’s Play Index for most of the stats in this post. Subscribe to the Play Index here.